To purchase catalogue please contact info@rosenbergco.com or 212-202-3270.

“Without poets, without artists . . . everything would fall apart into chaos. There would be no more seasons, no more civilizations, no more thought, no more humanity, no more life even; and impotent darkness would reign forever. Poets and artists together determine the features of their age, and the future meekly conforms to their edit.”

— Guillaume Apollinaire

In 1913, when Guillaume Apollinaire proclaimed that artists were the defenders of mankind, the future was Promethean, and the present was in love with speed, machines, and drunk on cosmopolitan novelties. It was a stateless Guillaume Apollinaire, born in obscure circumstances as Wilhelm de Kostrowitzky, who became the spokesman for the then-visionary universe of the literary and artistic world, blurring the borders of the pen and brush. Apollinaire could not have known how tragically naive his words would prove to be: less than a year later, the world would be overtaken by the “impotent darkness” of the First World War. Poems and paintings could not prevent the collapse of civilizations nor the death of millions—including Apollinaire himself.

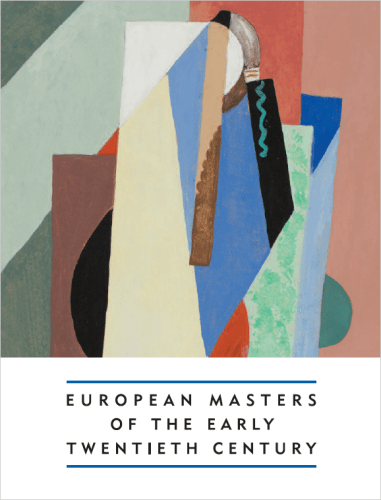

Attempts to define artistic currents and experiments of the period yielded terminology that proved more obscure than helpful. “Modernism,” used as short-hand to express rejection of the old ways, was insufficient to capture the seemingly limitless exuberant creativity. “Modernism” spawned a litany of “isms”—Dadaism, Surrealism, Cubism, Orphism, Futurism, Expressionism, Vorticism, and Suprematism, to name but a few. These titles were more than pure theory, and were largely intended to evoke new sensations, calling upon the viewer’s sixth sense. This was so, even though several artists published pamphlets, manifestos, and essays describing the basis of their so-called new movement—such as Gleizes and Metzinger’s Du Cubisme in 1912, or the Blast publications by the Vorticists in 1914 and 1915, or Marinetti’s Manifesto del Futurism in 1909. The ease with which participants categorized and labeled these movements belies a porous and fluid art world in which artists tested and combined aspects of each of these supposedly distinct movements. These boundaries are artificial, and may in fact preclude understanding: for example, Henry Valensi’s 1930 La Casbah d’Alger combines the unearthly qualities of Surrealism, the structural play of Cubism, and the garish colors of Fauvism, yet Valensi is usually categorized as simply a Cubist. In a few years, the Cubists’ playbook had moved far from its intellectual constructs, but was still firmly based on the precepts of more “classic” works such as Gleizes’s 1915 Portrait de Florent Schmitt. Whether the “Cubist” label (a term Apollinaire coined) is appropriately used or not with respect La Casbah d’Alger is ultimately not as important as recognizing that it unquestionably fits within the aesthetic of the period by reinventing forms and colors. It is reinvention without ever turning away from the concepts on which art history is built.